Peloni: A very important high level review of recent events in which US policy aligns actions in the Caribbean with policy shifts in the Middle East.

What’s wrong and right with the world of national security and power rhetoric.

J.E. Dyer, a retired Naval Intelligence officer, blogs as The Optimistic Conservative, Oct 27, 2025

Feature image: U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Felix Garza Jr. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

Feature image: U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Felix Garza Jr. (Via Wikimedia Commons)

These will be a pair of Ready Room notes on the headline topics. More people with each passing month seem to be catching up with the OODA loop of current events (while others like the Carlson/Owens fold are pegged on bizarre takes that have nowhere to go). And so much is always happening that it’s not a good use of time to try to write at length about most of it.

But there are some points worth making about the headline topics. So, diving right in, the carrier situation.

Ping One: A carrier to Venezuela

USS Gerald R Ford (CVN-78), which Is currently deployed in the Mediterranean, was ordered on Friday 24 October 2025 to the Caribbean to enter the counterdrug fight there. Ford will bring at least one Aegis destroyer escort (four deployed with the carrier in June), one of which will presumably be USS Winston S Churchill (DDG-81), which has been serving as the carrier’s air defense commander during this deployment.

Two other escorts from the Ford Strike Group are operating independently in or near the Middle East, and will probably remain there to continue their tasking.

Ford has the typical complement of 50 strike-fighters (F/A-18 Super Hornets), along with airborne early warning, electronic warfare, and helicopters embarked with its air wing, CVW-8. It’s a significant ramp-up of the firepower offshore, and has to send a major signal.

The very unusual signal is moving a carrier from the Eastern to the Western hemisphere in order to have it available for potential combat in the Americas. That suggests a purpose off Venezuela significantly larger than merely continuing to pick off speedboats. Considering there’s already an amphibious ready group, USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) ARG, with the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit embarked, plus some four more surface escorts and a littoral combat ship, an attack submarine, Air Force AC-130J gunships and Marine Corps F-35Bs in Puerto Rico, and an extensive cast of support aircraft and drones, this is a very large dedicated force by today’s standards.

However, I don’t think the slow, steady build-up off Venezuela is about mounting an invasion. I urge readers to digest that sentence as many times as necessary to cease thinking the “invasion” thought.

I think it’s about accumulating a dominant presence to deter operations against the U.S. for which Maduro and other parties might see a need. While keeping the deterrent force in place, where it can intercept desperation moves by Maduro or his extra-hemispheric patrons, the Trump planners would also have an array of options for accelerating the fight against the cartels. In other words, this is operational containment to control the escalation of a fight Trump intends to be a decisive one.

Venezuela has been thoroughly penetrated by and in league with all of Iran, Russia, China, Cuba, Hezbollah, and Hamas for between 15 and 20 years, depending on which of those marauding actors we’re talking about. The penetration was well underway during Hugo Chavez’s radical socialist years, and has continued, in some ways with increasing intensity, under Nicolas Maduro.

As early as 2010 there were clues about a remote site in northwest Venezuela possibly being prepared to host missiles for Iran. Subsequent developments on that head have not emerged since 2011, but regular flights between Iran and Venezuela, and visits by Iranian “dark fleet’ merchant ships – all in violation of U.S. sanctions – have offered plenty of opportunities to move materiel, weapons, and personnel (e.g., elements of Iran’s paramilitary Qods Force) into the country.

Hezbollah and Hamas are known to participate in narcotics cartel operations in Venezuela, as well as elsewhere in Central and South America (see here, here, here. Note: the first link from 2020 has a list of links with extensive documentation of Iranian proxy activity in Latin America, and that of China, Russia, and Iran. The article was posted because Trump was launching a major campaign against the cartels at the time. That effort is not much remembered today, but in 2025, Trump has basically resumed it, and ramped it up and retooled it).

Both terrorist organizations have been embedded there for years, finding the operations a convenient way to generate cash and maintain ties useful for spying and preparing a “battle space” for future terror operations in the Americas. There is also credible reporting that Iran brokered the migration of tens of thousands of Syrian sympathizers to Venezuela over the past decade, the height of Tehran’s involvement and influence in the former Assad regime. The interventions amounted to population-swapping, in fact, as thousands of Venezuelans also migrated to Syria.

Maduro has been complicit in these activities, and indeed, as affirmed by Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado in an interview with Fox’s Maria Bartiromo on 26 October 2025, he is running the major cartels there, including Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua.

Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado in an interview with Fox’s Maria Bartiromo on 26 October 2025.

Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado in an interview with Fox’s Maria Bartiromo on 26 October 2025.

That’s when he’s not hosting Russian military visits and making agreements with China that bring weaponizable industrial infrastructure into Venezuela. In a most noteworthy move, reported in September 2025, China dispatched a naval hospital ship to Venezuela – a move that might seem benign if you don’t know what China uses these movements for. In Beijing’s modus operandi, such support vessels in foreign waters can become a pretext for a “defensive” presence of armed protective forces, including combat ships of the PLA Navy (PLAN). (Russia has operated this way for decades, including its former-Soviet Union days.)

China has thus deployed a beard for such a purpose – a use the offshore oil rig mentioned at the link above could also be put to. Security for the Chinee fishing fleet is another handy pretext, although Chinese fishing vessels tend to congregate further south along South America’s east coast. (China has made naval deployments around South America punctuated by port visits in recent years, so having such ships in the theater would not be unprecedented. Deploying them for a dedicated “defensive” mission would be, however.)

As outlined in a previous article here, China also has the capability to deploy missiles and drones in shipping containers, either in nearby ports or at sea, that could cover the entire Caribbean and Venezuelan coast with pop-up threats, even without the presence of warships.

If you’re looking for a reason why China would go to such trouble, recall that Beijing is behind much of the extremely lucrative fentanyl trafficking into the U.S., in which Tren de Aragua is heavily involved. Mexico is working with the U.S. on stifling that flow of contraband. China is facing the genuine prospect of seeing its illicit trade much reduced there. Maduro is not cooperating with the U.S., and would be of increased importance to China as the funnel through Mexico is tightened.

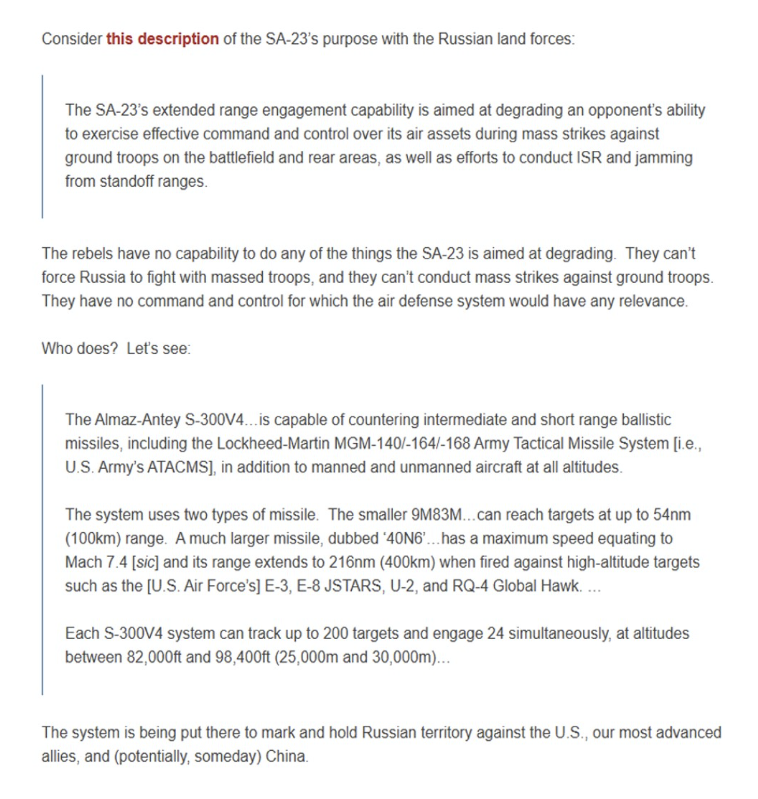

Venezuela would also use Russian-bought air defense weapons and counter-air fighters (Su-30s) in an armed reaction to U.S. activities, for which Russian advisors and maintainers are likely to be in-country. Besides the point-defense anti-air missiles (i.e., the Igla-S), note in particular that Russia sold the Russian Army’s version of the S-300 (the Almaz-Antey 2500 S-300VM, NATO designation SA-23) to Venezuela back in 2013. (Scroll down to the bottom at the link. Apologies that the old article at Liberty Unyielding no longer has its images intact.)

The Almaz-Antey S-300V-series added a ballistic missile defense capability to the baseline S-300, a capability at the time geared to the short-range threat from the U.S Army ATACMS (the baseline system for which the HIMARS version was developed, lately so much in the news as a weapon system for Ukraine). As a measure of the seriousness Russia assigned to deployment of that weapon system, see the commentary in this article from 2016, when Moscow deployed its own S-300V-series/SA-23 missiles to Syria (in the S-300V4 variant). Selling the Army version to Venezuela probably reflected both parties’ considerations: Maduro’s, and Moscow’s, that it would one day be necessary to fight the United States in Venezuela.

Screen cap from source described in the text, discussing Russia’s employment of the army version of the S-300V-series air/missile defense system. Click to enlarge for legibility.

Screen cap from source described in the text, discussing Russia’s employment of the army version of the S-300V-series air/missile defense system. Click to enlarge for legibility.

(Apologies again: the linked article at Scribd has been deleted since the Liberty Unyielding piece was published. The original article at that link was by a Russian author of a series on military weapons topics, whose body of work was serious and authoritative. Unfortunately, the untimely suicide of my desktop computer in 2018 resulted in the loss of background notes on my 2016 article.)

More ominously, reporting in August 2025 suggested Russia was in the process of deploying (or preparing to deploy) “Oreshnik” intermediate range ballistic missiles to Venezuela, which would have the reach to get to the northeastern and central United States (see the first topic and map in the 14 August Ready Room).

Maduro has had regime security from Cuba for years (said to number some 15,000 operatives), and reportedly uses the Cubans to harass, detain, and keep Venezuelans under armed surveillance.

Finally, see my article from 2024 on a little-noticed excursion in April and May by Iran’s converted container ship Shahid Mahdavi, outfitted to use deck-container positions to transport and launch container missiles. In January 2024, Iran used the ship to launch container-borne ballistic missiles from the Northern Indian Ocean to an impact point inside Iran. During the April-May deployment, Shahid Mahdavi transited to within missile range of Diego Garcia, and afterward was ostentatiously announced by Iranian media to have done so. The implied threat was clear. It’s equally clear in relation to other potential deployment areas, and the use of lower-profile and more anonymous Iranian container ships. China (and Russia) aren’t the only potential sources of container-borne missiles and drones.

There is a real and growing threat out there to prepare for. Venezuela’s is not a solo operation by Maduro. Every aspect of it has the potential to offer superficial political justification for foreign activities. One possibility that can’t discounted is that the foreign threat nations could menace the Panama Canal. Interdicting that before it even got started would be the ideal response.

If Trump is seeking to break the back of the cartels in Venezuela – which inevitably means breaking the Maduro regime’s as well – a deterrent U.S. presence big and dominating enough to put a “KEEP OUT” sign on Venezuela and its Caribbean coast is very much in order.

I don’t think Trump’s intention is to invade or even raid Venezuela. I think he’s putting sufficient force there to warn the worst actors on the planet not to make it necessary for him to.

Carrier out of the Middle East and European theaters

This second part of the first ping needs to be featured separately for its full import to be felt. It’s this: the Ford carrier strike group has left the EUCOM/CENTCOM theaters headed for the SOUTHCOM theater in Latin America and the Caribbean, and there’s no carrier or amphibious group in the Europe-Middle East region at all, nor is there a prospect of one. (The USS Nimitz (CVN-68) Strike Group is in INDOPACOM in the South China Sea, but is wholly absorbed in projecting U.S. power there, and in any case is returning home from a deployment that included CENTCOM.)

Yet this circumstance is neither as remarkable nor alarming is it would have been at any time since the Truman Doctrine was declared nearly 80 years ago.

Why? Because with Israel effectively dominating Gaza, and after the massive Israeli and U.S. strikes in June 2025 on Iran’s military and nuclear weapons infrastructure, and Iran’s and Russia’s abrupt retreat from Syria with the collapse of the Assad regime, the major features of the geopolitical landscape have greatly changed in that area.

There’s breathing room now in Southwest Asia to make a carrier presence less necessary than it’s been for decades. The U.S. still has substantial forces in CENTCOM, and on-call from EUCOM.

But – and here’s the key – Trump can actually fight both the drug trade and Hezbollah, Hamas, and Iran in the Americas, and do so even more effectively here. He’ll be attacking their center of gravity for power projection in the Western hemisphere: the drug trade and Maduro’s connection to it, which brings in a territory (Venezuela’s) whose loss to the bad guys has very high cost. And Trump will be addressing it where it could pose the most direct threat to the United States.

Breaking the threat’s back here pays dividends in both hemispheres, and starts where America needs it to start: in ours.

The decisive fight to neutralize Hamas, rock Hezbollah on its heels in Lebanon, and badly cripple Iran’s regime is paying off big-time. (I suggest getting a “Thank you, Israel” T-shirt. If Jerusalem had contented itself with mowing the grass once again in Gaza after the horrendous atrocity of 10/7, we’d still be facing U.S. security problems we had little opportunity to aim strategically concentrated blows at.)

Also important: the Russia-Ukraine problem can’t be contained by carrier power anyway. The geography of it doesn’t allow that; the closest a U.S. or other NATO carrier can get is the Northern Aegean Sea, and coordinating any useful operations from there would be a nightmare of operational purpose and questionable political accommodation.

Whereas there are U.S. and allied strike-fighters, missiles, drones, and missile defense sites all over Europe, including Turkey, not to mention warships off the coasts, in sufficient numbers and of sufficient quality to deter and deal with rogue activities by Russia, if those assets are backed by credible will. Given the nature of the problem, not having a carrier in theater doesn’t leave a big hole in NATO deterrence.

There’s a lot more to say, but we can’t linger here all day. The sign-off point on Ping One is that Ford just left Split, Croatia on Sunday, and could get to Venezuela in about a week if Churchill gets regular drinks off a supply ship and keeps up at a dead sprint. My guess is the transit will be done in a slightly less frenetic fashion. Maybe a genteel 9-10 days.

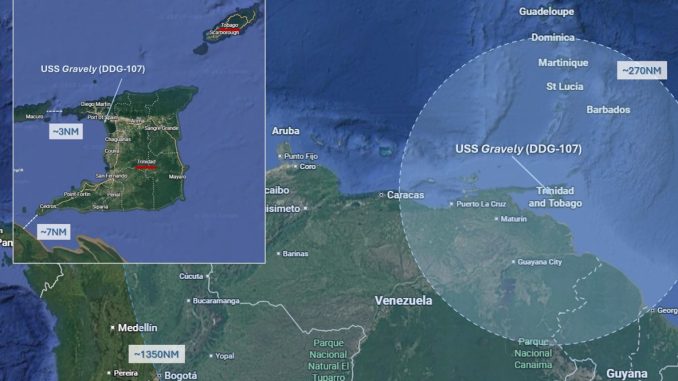

Here’s a bonus visual to punctuate the sign-off. A detachment of 22nd MEU Marines, embarked in USS Gravely (DDG-107), has just pulled into Trinidad and Tobago for a timely fraternal interlude (joint exercises) with our good friends there. If you’re not familiar with how close T&T is to Venezuela, enjoy.

USS Gravely‘s (DDG-107) and embarked U.S. Marines’ proximity to Venezuela while in Trinidad and Tobago for the Oct 2025 port visit. Trinidad’s distance from Venezuela is about 3 nautical miles at the narrowest (see map inset). The two narrow straits hem in Venezuela’s Gulf of Paria, west of Trinidad. The U.S. units are in Port of Spain, as indicated. The range rings for Gravely show (a) the minimum reach of the Maritime Strike Tomahawk anti-ship missile in the Block Va (“five a”) variant, at about 270NM; and (b) the maximum reach of the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile at about 1350NM. Gravely‘s exact loadout is not reported; since she’s a Flight IIA hull I imagine she has the most modernized Block Va package. Click image to enlarge for legibility. Google map; author annotation.

USS Gravely‘s (DDG-107) and embarked U.S. Marines’ proximity to Venezuela while in Trinidad and Tobago for the Oct 2025 port visit. Trinidad’s distance from Venezuela is about 3 nautical miles at the narrowest (see map inset). The two narrow straits hem in Venezuela’s Gulf of Paria, west of Trinidad. The U.S. units are in Port of Spain, as indicated. The range rings for Gravely show (a) the minimum reach of the Maritime Strike Tomahawk anti-ship missile in the Block Va (“five a”) variant, at about 270NM; and (b) the maximum reach of the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile at about 1350NM. Gravely‘s exact loadout is not reported; since she’s a Flight IIA hull I imagine she has the most modernized Block Va package. Click image to enlarge for legibility. Google map; author annotation.

Ping Two: The Rhetoric and the Reality

This observation is important.

It has to do with the public discussions by Trump officials of U.S. policy on Gaza and the Middle East, which regularly disappoint and frustrate knowledgeable and well-meaning observers. Knowing the treachery nations like Turkey and Qatar have frequently engaged in, and their bad records on problems like Syria, the Kurds, Palestinian Arab terrorism, and basic human rights, it’s understandable that the sometimes (OK, often) fatuous-sounding rhetoric is like nails on a chalkboard.

It’s not just the rhetoric, of course. It’s the policy direction indicated by speeches, affirmations, and proposals, when taken at face value as each instance pops up. Too often it seems – there’s no other word for it – stupid. We’re surely not thinking of allowing a military or even any other on-the-ground presence in Gaza of forces that answer to Recep Tayyip Edogan, right? In fact, why are we contemplating such foolishness as a multinational peacekeeping force in Gaza that sounds exactly like the counterproductive UNIFIL in southern Lebanon? And is it really necessary to slather Qatar in so much butter that there’s no ungreased spot to latch onto, if Doha wants to get slippery on us?

These are legitimate questions. I offer a couple of thoughts to help deal with them, however.

The first has so far been comprehensively true, though it’s still unnatural to keep it in mind. It’s simply this: none of the weirdly convivial acclamations being launched by American envoys at our sour-faced regional partners with poor records for reliability and common interests has actually produced the evil outcomes predicted for them.

We keep batting around complaints that the plan of the moment and its rhetoric are so stupid, everything’s hurtling toward failure. And yet the failure never comes. Sure, Hamas keeps breaking ceasefires right on schedule, but Israel then jumps right in and starts pounding Hamas. Netanyahu isn’t being held back in that regard in a way that compromises the prospect of long-term victory.

Equally importantly, as I continue to point out, neither Qatar nor Turkey (nor Egypt, for that matter) is being allowed to run rampant through the post-combat settlement with any likelihood of getting its own way, against Israel’s interests. Again and again, since January 2025, the common assumption has been that Qatar, at the very least, is buying the outcome it wants. But Qatar hasn’t gotten any such outcome up to now. It’s all questionable-looking interim moves and process. Qatar’s not in charge and it’s not toting contraband political wins off the field in unmarked bags.

Vigilance is in order, as always, but the fears just aren’t bearing dark, rancid fruit. Explaining that is too much to try to do in this treatment, but the pattern hasn’t worsened. It’s uncomfortable, because we’re used to carefully stringent-sounding, conventional wording being sent off across a high-wire, instead of the stream of extravagant nonsense our envoys keep producing. The old standard of rhetoric had the advantage of being comforting and familiar.

But it was also hollow and ultimately meaningless. When the Biden administration said “we’re with you to the end and we’ll never leave or forsake you and, doggone it, we really like you too,” while nevertheless delaying and suspending and making excuses about missing arms deliveries to Ukraine and Israel, I promise you, no one was deceived that those familiar, ritual affirmations actually heralded some credible, tie-breaking policy outcome. What everyone knew, rather, was that they didn’t.

I can’t account for the unnecessary slurping that accompanies press announcements of Middle East policy updates by Trump’s team (though I have my suspicions about some of it. One thing to keep in mind is that keeping the front door open for max participation by the various parties helps discourage the sneaky backdoor problem). But it hasn’t had the concrete effects outlined in pessimistic predictions.

The second and last point is that Iran’s hold on Syria has been broken, and the regime’s progress toward a bomb interrupted, and that changes everything. The old assumptions about inevitable effects are no longer written in stone. Even Hezbollah’s reality, probably the least affected among the Islamic revolutionary regime’s proxies, has taken some body blows with the upheavals and resets in Syria.

And circling back to Ping One, a new front is being opened on the other side of the world against Iran and its power-projection enterprises. A key problem for Tehran and the proxies is that their local host is Nicolas Maduro. Against an alerted United States using our power in our own back yard, Iran and its proxies have no real leverage. The only advantage they could have is not being noticed.

But the unacceptable impact of the drug trade and other cartel trafficking on the U.S. has guaranteed their being noticed – and it guarantees that they, in their own right, have no bargaining chips in the Western hemisphere situation. It’s between the U.S., Maduro, the cartels, and China. But it directly affects Iran and its proxies in the Levant – dividing their interests and priorities, and wreaking havoc on their incentive structure. I wouldn’t ignore that.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.