Peloni: The legacy of Yehudit Katsover and Nadia Matar is that of legends. We are lucky to have had their key leadership, moral fortitude, and keen insights. They inspired a revolution which was slow building but has had victories in great and small ways.

Prof. Aryeh Eldad , Maariv January 26th

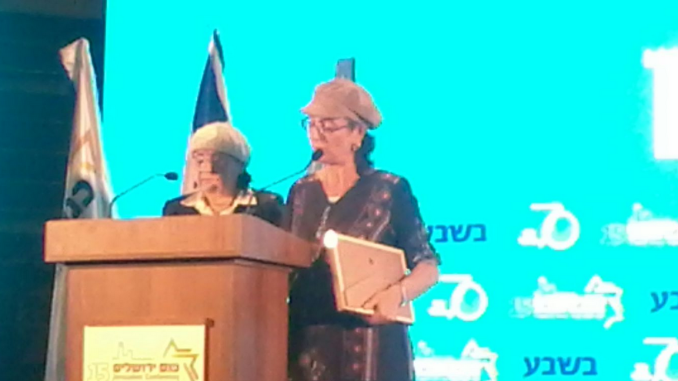

Jerusalem Conference Nadia Matar and Yehudit Katsover. By ?? ???? – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia

Jerusalem Conference Nadia Matar and Yehudit Katsover. By ?? ???? – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia

Translated into English by the Sovereignty Movement:

Settlement in Judea and Samaria experienced a low point following the Disengagement, the evacuation of outposts, and international pressure. But today, an unprecedented momentum of construction, regulation, and establishment of new communities is taking place.

Twenty years ago, Jewish settlement in Judea, Samaria, and the Gaza Strip was at a historic low point. The Disengagement—engineered by Ariel Sharon—uprooted 25 communities from the Gaza Strip and northern Samaria and handed these areas over to full Arab control. Thus, Hamas was able to turn the entire Strip into a massive terror base, and Jenin and its surroundings into active terrorist hubs.

Ehud Olmert replaced Sharon after his collapse and sought to continue the momentum of destruction and uprooting. He promised “convergence” in Judea and Samaria as well. His failure in the Second Lebanon War and the criminal proceedings that eventually sent him to prison ultimately blocked his intention to dismantle the settlements and establish a Palestinian state. In his final days in office, Olmert still tried to reach a dangerous withdrawal agreement from Judea and Samaria.

But Abu Mazen, unwilling to sign with someone already on his way out, placed his hopes in Tzipi Livni and her promises. When she too failed to reach the top, the immediate danger of a comprehensive withdrawal and the establishment of a Palestinian state in the heart of our homeland passed.

The governments of Benjamin Netanyahu and Bennett–Lapid did not wish to deal with this issue. But Jewish settlement suffered a severe blow. Entire communities were destroyed. Radical left-wing organizations repeatedly petitioned the High Court of Justice demanding the demolition of outposts and neighborhoods, and often received a sympathetic hearing. This was the case in Amona, Migron, the Dreinoff Houses in Beit El, and the Netiv HaAvot neighborhood in Gush Etzion. The High Court joined the struggle against settlement. In those days, I was involved in efforts to block these destructive moves—mostly with only partial success.

From the outside, pressure from hostile American administrations prevented the establishment or legalization of new outposts. Netanyahu governments—until the current one—mostly gave in to these pressures.

At the time, the Civil Administration saw itself as the main obstacle to any Jewish settlement efforts and in most cases sided with the Arab side. It adhered rigidly to its interpretation of the Oslo Accords long after Israel and the Arabs had ceased to believe in them. The IDF, reflecting the political leadership, viewed settlement as a burden rather than an asset and believed it was possible—and even desirable—to evacuate most IDF camps from Judea and Samaria. The evacuation of bases that began after the Oslo Accords, not only from Area A in Arab city centers, continued into the early 2000s from Area C as well, which was supposed to remain under full Israeli security and civilian control.

Some bases were evacuated during the Intifada years, when the IDF believed they were difficult and costly to maintain. Their evacuation was completed following the Disengagement. Thus, the Paratroopers’ base in Sanur, Golani’s Bezeq base, Camp Gadi in the Jordan Valley, Camp Dotan in northern Samaria, Adoraim in southern Mount Hebron, Umm Daraj in southern Buka’a, and Camp Shdema east of Gush Etzion were evacuated.

The current government, Israel’s 37th, deserves much praise for the unprecedented settlement momentum it is generating in Judea and Samaria. Even its most outspoken opponents cannot deny its achievements in this area—though to them this may be yet another reason for their opposition.

Ministers Bezalel Smotrich, Orit Strock, Ze’ev Elkin, Israel Katz and their colleagues; Ze’ev Hever (Zambish), head of the Amana settlement movement; the regional councils of Samaria, Binyamin, Gush Etzion, Mount Hebron, and the Jordan Valley; and above all, thousands of settlers in hundreds of outposts and agricultural farms—all these and many others have changed the map. Large empty areas are being taken in a race to seize and hold the land of Israel, in the face of Arabs who receive encouragement and funding from Ramallah and Europe.

At the same time, the government and the Civil Administration have increased the pace of demolishing illegal Arab structures in Area C that were built to block Jewish settlement. Some abandoned IDF bases have already been taken over by settlement groups. After the repeal of the “Disengagement Law” for northern Samaria about three years ago, the uprooted communities are being rebuilt—such as Homesh and Sa-Nur. There is also a government decision to reestablish Ganim and Kadim near Jenin.

The Inauguration of the Community of Yatziv (Camp Shdema)

This week, I participated in a ceremony for the affixing of a mezuzah and the inauguration of a new community called “Yatziv,” located adjacent to Camp Shdema, east of Gush Etzion. The story of this place is an amazing example of political and military short-sightedness on the one hand, and of civic perseverance and determination, rooted in strategic and settlement-oriented vision, on the other.

During the Mandate period, the British established Camp Shdema on the peak of a mountain overlooking its surroundings, east of Bethlehem and above the transportation route that today connects the communities of eastern Gush Etzion with Har Homa and Jerusalem. They understood that they needed to be on the ground in order to prevent smuggling and the organization of Arab gangs in the Judean Desert.

When the British left, the Jordanian Legion entered, and after Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, the camp became the base of the Paratrooper Nahal Battalion—Battalion 50. In 2006, perhaps as part of Olmert’s “romance” with Abu Mazen, or perhaps due to an internal IDF decision, the camp was evacuated, abandoned, and within a few days looted by Arabs from Beit Sahour. Only the skeletons of the British buildings remained. Nature—human and national nature as well—does not tolerate a vacuum.

The Palestinian Authority decided to take over state land that Israel no longer wanted and planned to establish a “children’s hospital” there for the Bethlehem area. The site was far from the region’s cities and had no reasonable access road from the west. It was clear that this was a pretext for taking control of the area, something that would “look good” in the eyes of the international community.

The IDF withdrew. The state sought to give up the area as a gesture to the Palestinian Authority, which began entering with both feet and with bulldozers. Only two women stopped them: Yehudit Katsover from Kiryat Arba and Nadia Matar from Efrat. They founded the organization “Women in Green” and now head the Sovereignty Movement. They hold no official position or status.

In 2008, journalist Hagai Huberman exposed the government’s intention to hand over the army base to the Palestinian Authority, even though it is located in Area C.

Yehudit and Nadia understood—unlike the country’s leaders and the IDF leadership at the time—what this meant. They established the “Committee for a Jewish Shdema,” recruited dozens of volunteers, and came to the abandoned camp. They cleaned and renovated it somewhat, prepared lecture rooms, recruited lecturers, and began holding seminars there on Fridays. I, too, had the privilege of teaching in those seminars.

The IDF responded quickly: it declared the area a “closed military zone,” issued administrative restraining orders against them, demolished tents and temporary structures they had built, evacuated and even confiscated their equipment, detained them, and arrested them. But they returned again and again.

Why? After all, the IDF had decided it had no interest in the site. Why did it suddenly become a “closed military zone”? Here, the IDF served as a tool of the Olmert government. But Ehud Barak, defense minister in Netanyahu’s government formed in 2009, also continued to harass them. He too hoped—and apparently still hopes—that a “Palestinian state” would arise there.

Eventually, even the IDF understood. In 2010, the army returned to the camp. Salam Fayyad’s plan to take over the area was thwarted. Nadia and Yehudit moved on to their next mission.

This week, they attended the inauguration of the new community, “Yatziv” (a temporary name), adjacent to the military camp. And why not inside the camp itself, most of whose buildings are empty? The IDF apparently rediscovered its strategic importance and is unwilling to give up even a small part of it. Perhaps this is part of the ideological, strategic, and security shift that the Civil Administration and the IDF have undergone following October 7.

What have we learned? That even when politicians and generals make huge mistakes, sometimes two women who see reality clearly, and who are determined and devoted to their goal, are enough to change reality, turn back a wheel that has gone off course, and return it to the right path.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.