Peloni: Fantastic article!

Herzl recognized nationalism as a powerful but neutral tool, capable of bringing out the best in us – or the beast in us.

Gil Troy | Feb 12, 2026

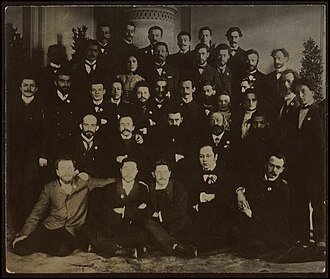

Herzl and the ‘Democratic Fraction’ at the Fifth Zionist Congress. A group photograph of Herzl with members of the Democratic faction of the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel, 1901. The photograph shows, among others, Chaim Weizmann, Martin Buber, Berthold Feibel, Ephraim Moshe Lilin. Photo by Unknown author – National Library of Israel, Public Domain, Wikipedia

Herzl and the ‘Democratic Fraction’ at the Fifth Zionist Congress. A group photograph of Herzl with members of the Democratic faction of the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel, 1901. The photograph shows, among others, Chaim Weizmann, Martin Buber, Berthold Feibel, Ephraim Moshe Lilin. Photo by Unknown author – National Library of Israel, Public Domain, Wikipedia

On February 14, 1896, the first 500 copies of Der Judenstaat: Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage – The Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question arrived at Theodor Herzl’s home. “I have the solution to the Jewish question,” this Viennese journalist and playwright exclaimed during seven months of frenzied writing. The Jewish Question was two-dimensional: Jew-haters couldn’t figure out why Jews always stand out – and Jews couldn’t figure out why Jew-haters can’t stand them. “I know it sounds mad; and at the beginning I shall be called mad more than once—until the truth of what I am saying is recognized in all its shattering force.”

Some books, like Moby Dick The Great Gatsby, and Elie Wiesel’s Night, have long runways – popping after years of neglect. The Jewish State was an instant sensation. Translated into seven languages, it inspired many Jews – and infuriated many others. But 130 years later it’s clear: the People of the Book found their bookish savior.

Herzl’s solution was simple. “The idea which I have developed in this pamphlet is an ancient one,” Herzl wrote: “It is the restoration of the Jewish State.” Judaism was not just a religion. Until the Jewish nation had a state, it would be hard to respect the Jews – and too easy to victimize them.

Herzl defined the Jews elegantly: “We are a people—one people.” Today’s divided America, that should be building to its 250th anniversary together but can’t even celebrate a Super Bowl half-time show without bickering, could benefit from his insight into what makes a nation. “I do not think a nation must speak only one language or show uniform racial characteristics. This quite moderate definition of nationhood is sufficient. We are a historical group of people who clearly belong together and are held together by a common foe.”

Herzl explained that a flag was not just “a stick with a rag on it…. With a flag one can lead men wherever one wants to, even into the Promised Land.” The flag carried a people’s “imponderables,” their “dreams, songs, fantasies,” because “visions alone grip the souls of men.” While respecting individual rights, he believed that individuals cannot help themselves “politically nor economically as effectively as a community can help itself.”

True, especially for Jews, “distress binds us together.” But with Herzl’s Zionist Jew-jitsu, in rallying as a people, “we suddenly discover our strength.” Once they reunited, the Jewish people would be “strong enough to form a state, and a model state at that.”

Herzl’s liberal-democratic nationalism was steeped in such altruism. Concluding this 1896 Zionist manifesto, Herzl articulated that quintessential democratic dynamic: as a people huddle at home together, liberal-nationalism helps them improve the world. Refusing to be a Reactive Zionist, Herzl tapped liberal nationalism’s constructive potential: “We are to live at last as free people on our own soil and die peacefully in our own homeland…. And whatever we attempt there for our own welfare will spread and redound mightily and blessedly to the good of all humanity.”

With the Austro-Hungarian Empire fragmenting, watching Jew-hatred and xenophobia bewitch Europe, Herzl found nationalist inspiration in America. His faith in technology blurred with his faith in what we could call America’s dreamocracy – a country, like the Jewish state, that is tribal yet aspirational. “The word ‘impossible’ already seems to have disappeared” there, Herzl gushed, jazzed that modern “contrivances” make it easy to “transform the desert into a garden…. America offers countless example of this.” Looking toward “the young political giant across the sea,” he assumed the “support” of “the freest nation on earth,” would “make the road to Zion easier.” More than practical assistance, he valued the ideological role-modeling.

In that turn-of-the-century era of “magnificent renaissance,”Herzl gave the Jewish people what they needed. After centuries of leaps of faith, trusting God to save them, Zionists took a liberal-democratic leap of hope to save themselves. Hope fosters collective confidence in tomorrow – while imposing a sense of responsibility today: rather than throwing up your hands, you lift up your eyes as you roll up your sleeves.

Today, dejected Americans, from left to right, should absorb the optimism from Herzl that Herzl – and countless others — absorbed from America. America’s political polarization reflects a loss of hope and a lack of trust. We cannot flourish together if we’re divided, with some so romanticizing the past they see nothing America should change, and others so hostile to the present they doubt America’s capacity to change.

The America of possibility Herzl admired would reject this new nihilism wherein progressives don’t believe in progress and conservatives don’t conserve institutions.

Herzl recognized nationalism as a powerful but neutral tool, capable of bringing out the best in us – or the beast in us. He died, in 1904, at 44, four decades before Jews experienced nationalism at its most barbarous through Nazism and at its most liberating through Zionism and Israel’s establishment in 1948, three years after Germany’s defeat. Herzl appreciated that the “world belongs to the hungry,” to those graduates of “the good American school of the struggle of life,” ready with big dreams and hard work to break “away from miserable circumstances.”

On this 130th anniversary of Der Judenstat, and building to July 4, 2026, Americans should replicate Herzl’s leap of hope. Every day, when ten million Israelis awake in their beds, at home in their homeland, most know that every construction site they see, every start-up that starts, and every new investment from afar, helps explain why they are safer, freer, and more prosperous than their great-grandparents would have dared imagine. Similarly, Americans should look around at home, appreciating that most of us are far better off than our ancestors were, thanks to America’s liberal-democratic nationalism, which never promised perfection, only the freedom to keep dreaming and trying, together.

Professor Gil Troy is an American presidential historian, the editor of the three-volume set, Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings, and, most recently, “To Resist the Academic Intifada: Letters to My Students on Defending the Zionist Dream.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.