Walter E. Block and Oded J.K. Faran

Photo by Oleg Yunakov – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia

Photo by Oleg Yunakov – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia

On October 13th, 2025, 21 Tishrei 5786, during the festival of Sukkot, after 738 agonizing days in captivity, 20 living hostages were returned to Israeli soil. In Tel Aviv’s Hostages Square, hundreds of thousands gathered. Across the country, traffic halted. Strangers embraced. A Monday morning transformed into something resembling a national holiday celebrating life itself.

While we rejoice in the return of these 20 souls, the focus here lies not in the political negotiations or military decisions that made this moment possible, but in a more fundamental question: What does this moment reveal about Jewish and Israeli identity?

A Country That Stops

The scale of this celebration demands closer examination. In cities from Haifa to Beersheba, ordinary citizens flooded public squares. Screens broadcast the handovers live. A woman in the crowd, interviewed by a reporter, said through tears: “I don’t even know them and I can’t stop crying.” The moment captured collective catharsis, something far deeper than staged patriotism or political theater.

Consider the question starkly: Can one think of any other modern nation that would entirely pause a Monday for the return of 20 people whom most citizens have never met?

The answer reveals something profound about Israeli society, and about the particular character of Jewish collective identity in the shadow of existential vulnerability.

The Collapse of Distance

In most societies, tragedy operates at different registers of emotional distance. A family member’s suffering is immediate and visceral. A neighbor’s pain elicits sympathy. A stranger’s crisis, however tragic, remains abstract, something one might read about, feel momentary concern for, then continue with the day’s events.

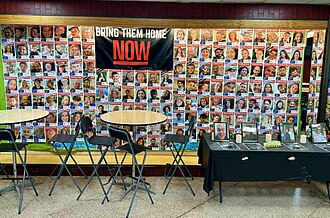

Israeli society defies this gradient of concern. The boundaries between “us” and “them” collapse when innocents suffer. These 20 hostages became everyone’s children, siblings, neighbors. Their faces stared down from every street corner on sun-faded posters. Their stories, told by anguished family members at weekly protests, became as familiar as one’s own family narratives.

The phenomenon runs deeper than nationalism. It reflects something more ancient and more binding: a sense that the collective body is incomplete when any of its members are in captivity. One cannot be fully free while others remain in chains.

The Ritual Dimension

From a social science perspective, yesterday’s scenes functioned as a national ritual, what Émile Durkheim might have called a moment of “collective effervescence.” These are the rare occasions when a society’s deepest values become visible, when abstract principles materialize into shared emotion.

The timing carries symbolic weight. That this return occurred during Sukkot, the festival commemorating divine protection during the Israelites’ vulnerable wandering in the desert, adds even further layers of meaning. The holiday itself is about fragility, temporary shelters, and the miracle of survival. The hostages’ return during this week resonates as more than coincidence; it reads as narrative completion.

Such moments serve as moral reckoning points. They answer the question: What does a society stand for? Yesterday, Israel answered: it stands for bringing its people home. It stands for the sanctity of innocent life. It stands for refusing to accept abandonment as inevitable.

Historical Context: When Nations Remember

Historical parallels are instructive in their rarity. When 52 Americans were released from Iranian captivity in 1981 after 444 days, yellow ribbons became a national symbol, massive crowds gathered, and the crisis had become what the Washington Post called a “national preoccupation.” Yet even then, the celebration took the form of sustained attention rather than a spontaneous national holiday.

In Israel’s own history, the 2011 exchange that freed Gilad Shalit after five years in Hamas captivity generated enormous public emotion. The 1976 Entebbe rescue became part of national mythology. But neither produced quite this phenomenon, an entire country pausing its Monday routine for the homecoming of 20 individuals virtually no citizen had never met.

What makes this different? The answer lies in the intersection of memory, trauma, and social structure.

Vulnerability as Social Glue

Israeli society exists in a state of what sociologists might call “sustained collective vulnerability.” Existential threats remain living realities rather than abstract historical memories. Mandatory military service means nearly every family has someone who could be in danger. The small size of the country means that degrees of separation collapse: everyone knows someone who knows someone. In many nations, there is “five degrees of separation.” Here, the separation is far less.

In such a society, the line between self and other blurs. When a soldier is captured, every mother sees her own child. When civilians are taken, every citizen recognizes their own vulnerability. The pattern recognition emerges from lived experience.

This shared vulnerability creates extraordinary social cohesion. It generates the kind of solidarity that sociologist Robert Putnam describes as “bonding social capital,” the tight, trust-based connections that bind a community together in the face of external threat.

The Shadows in the Celebration

Yet the complications must be acknowledged. Euphoria can simplify. In the joy of these 20 returns, those whose bodies have yet to come home cannot be forgotten, those families still waiting in anguish. Difficult questions about which hostages were prioritized and why must be asked. The ritual of return should not eclipse the ongoing duty of care, justice, and accountability.

Moreover, this intense collective identification has its costs. Societies bound by shared trauma can struggle to extend empathy beyond their boundaries. The same emotional mechanism that makes an entire nation weep for 20 returned hostages can make it difficult to see the humanity of others caught in the same conflict.

What Comes After the Holiday

The streets will return to routine. Traffic will resume its normal patterns. But the meaning of this moment should not dissipate with the celebration.

What Israel witnessed on that day was a society publicly declaring its values through ritual action. A nation that refuses to let the innocent become statistics, that treats each life as irreplaceable, that interprets solidarity not as slogan but as sacred obligation.

The question for observers is whether this solidarity can sustain itself beyond moments of return, whether it can animate not just celebrations but institutions, policies, everyday treatment of the vulnerable.

Twenty people came home on that day. Their return reminds us that in a society bound by memory and marked by vulnerability, every individual carries the weight of the collective, and the collective carries every individual home.

The meaning of yesterday’s holiday lies in the social forces that made it necessary and the identity that made it inevitable, beyond the politics that made it possible.

We asked above, “What does this moment reveal about Jewish and Israeli identity.” It is also of interest to compare this identity with that of Israel’s (hopefully former) enemies. The identity of the Jewish state is one of life. Life is precious. Life is the middle name of this country. Life is everything. And love too. Strangers do not hug each other in the middle of the street when there is no love. Tears, too. Full disclosure: in writing this essay and in rereading it too, our eyes brim over.

Stated Golda Meir: ““When peace comes we will perhaps in time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing our sons, but it will be harder for us to forgive them for having forced us to kill their sons. Peace will come when the Arabs will love their children more than they hate us.”

What of the neighbors of Israel? What motivates them? What turns their clocks? What gets them up in the morning, filled with resolve? It is difficult to deny that it is hatred, and death. Martyrdom is celebrated in those communities. You do not see any Israelis dancing in the streets, given the pulverization of Gaza, and the many deaths that occurred there (they were the fault of Hamas using civilians as shields, not of the IDF). That was not at all the case in all too many Arab countries on October 8, 2023. You have to hand it to these people, they are good haters; no excellent ones: world class. If there were an Olympic prize for hatred, they would merit the gold medal.

We can only hope and pray that a little bit of the Jewish soul will have rubbed off onto these folk with the ending of this war, which never should have begun in the first place.

Addendum

It cannot be denied, of course, that there was also considerable rejoicing when the folks on the Palestinian side of the hostage exchanges were sent back to Gaza and to Judea and Samaria (some mistakenly call this the West Bank). However, there is a disanalogy in so facile an equation of the two sides. Not a one of the Israeli hostages was a criminal. None were found guilty in a legitimate court of law. Not even Hamas itself ever claimed any such thing (apart from the fact that they consider all Israelis, all Jews, of whatever age, even babies who they murdered, as criminals. But these hostages were no more guilty, even in the Hamas view, than any other Jew or Israeli). In sharp contrast, in very sharp contrast indeed, the Palestinians released from Israeli jails were indeed criminals. They were either awaiting trial or found guilty, in civilized courts, of very serious crimes, up to, and including, actual murder..

Then, there is the issue of the motivation for the joy on the part of the Palestinians in receiving their recently released brethren. Was it love, happiness, something life-affirming? Or was it something darker, far darker. What on earth might this be? Could it be due, instead to the very opposite? There is, unhappily, precedent for such a motivation. For example, Yahya Sinwar was the mastermind behind the atrocity of October 7, 2023. Where was he located before that evil day? He was a prisoner in an Israeli jail who was released in 2011, along with 1,027 terrorist associates. This was in exchange for a single IDF soldier Gilad Shalit. He had spent five years imprisoned by Hamas, while Sinwar was incarcerated for 22 years.

It is beyond our knowledge as to how much of the joy on the part of the Palestinians was due to life affirmation, and how much to the hope for another Sinwar repeat. But given our knowledge of the Palestinian psyche, we expect quite a bit of it was due to hatred and death, not love and life.

Golda Meir was a keen observer of the Palestinian psyche. She wrote: “When peace comes we will perhaps in time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing our sons, but it will be harder for us to forgive them for having forced us to kill their sons. Peace will come when the Arabs will love their children more than they hate us.”

Conclusion

We cannot end this thank you note without mentioning the names of Donld Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, blessed may they be.

Sources

- Durkheim, Émile. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912) – Theory of collective effervescence

- Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000) – Bonding social capital concept

- Ganglani, Jay. “Who are the 20 hostages who were released by Hamas?” NBC News, October 13, 2025. https://www.nbcnews.com/world/middle-east/israel-hamas-gaza-who-are-20-surviving-hostages-rcna237251 – 738 days captivity detail

- NPR Staff. “Israeli hostages freed, hundreds of Palestinians released, as Trump hails ‘historic dawn.'” NPR, October 13, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/13/g-s1-93207/hamas-releasing-israeli-hostages – Hostages Square gathering, release details

- Magid, Jacob, Joshua Davidovich, and Shira Silkoff. “All 20 remaining living hostages return to Israel, after over 2 years in Hamas captivity.” The Times of Israel, October 13, 2025. https://www.timesofisrael.com/all-20-remaining-living-hostages-return-to-israel-after-over-2-years-in-hamas-captivity/ – Hostage return coverage

- National Museum of American Diplomacy. “Tie a Yellow Ribbon: The Origin of the National Response to the Iran Hostage Crisis.” August 30, 2023. https://diplomacy.state.gov/stories/yellow-ribbon-hostages/ – Iranian hostages 444 days, national preoccupation

- Beauchamp, Zack. “What history reveals about the current Israeli hostage crisis.” Vox, October 31, 2023. https://www.vox.com/23924044/israel-hamas-war-hostage-crisis-gaza-history – Gilad Shalit context

- Golda. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/664790-when-peace-comes-we-will-perhaps-in-time-be-able

- When and under what circumstances was Yahya Sinwar released from an Israeli prison? https://www.bing.com/search?q=9.%09When+and+under+what+circumstances+was+Yahya+Sinwar+released+from+an+Israeli+prison%3F&form=ANSPH1&refig=6941f65fc148405998eea2c60e909579&pc=LCTS

- Golda; https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/664790-when-peace-comes-we-will-perhaps-in-time-be-able

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.