T. Belman. Apparently Likud has offered Shaked an ambassadorship to a major European country in exchange for withdrawing from the election. She turned it down. What they should offer her is the role of Min of Justice.

2021’s vote saw a major drop-off in turnout from right-leaning and religious areas compared to 2020; in this campaign’s final month, Likud will focus on reversing that trend

In last week’s article, we analyzed the dilemma facing Prime Minister Yair Lapid in the final month of the campaign. This week, we will turn the tables and evaluate the campaign from the perspective of his challenger, Benjamin Netanyahu, analyzing his moves so far and what strategy he is likely to adopt in the final weeks as he seeks the elusive 61 seats that would (finally) enable him to form a right-wing government.

As a starting point, it is worth reviewing Netanyahu’s electoral history.

Indeed, while the former prime minister is an extremely divisive figure, one area where there is broad agreement is regarding his political acumen. His supporters frequently describe him as a “genius” and “magician,” while even his detractors often concede that he is a “supreme campaigner.”

His electoral record tells a slightly different story. In the 10 elections in which he has led the Likud party, he has only definitively “won” four (victory in the Israeli system is a vague concept, but here we will define it as being able to form a Likud-led government). Three have ended in defeat, and another three in stalemate.

Indeed, Netanyahu’s reputation as a political strategist par excellence is much more justified when it comes to his conduct in between elections, his survival instincts, and his sheer political endurance.

He has proved himself to be particularly masterful at navigating the daily challenges of Israeli politics (in particular the internal politics of his own party), keeping his coalition together and thus maintaining his grip on power longer than any other Israeli prime minister.

All of which is to say that while there is little doubt that Netanyahu is a supremely skilled politician, the same is not necessarily true when it comes to elections. While a forty percent success rate in national elections is nothing to be sniffed at, the idea that he always finds a way to pull the proverbial rabbit out of the hat and win is not backed up by facts.

Bibi’s campaign strategy

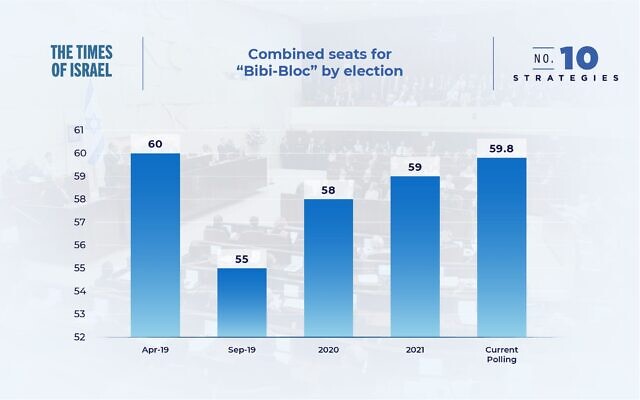

Approaching this campaign, Netanyahu and his team faced one obstinate challenge. Despite their best efforts – and getting extremely close several times – in four successive elections, the parties loyal to Netanyahu have failed to get to 61 seats.

Combined seats for MK Benjamin Netanyahu-led bloc.

Seeking to remedy this at the fifth time of asking, the Likud strategy appears to have been built on four main pillars:

1. Solidifying the bloc

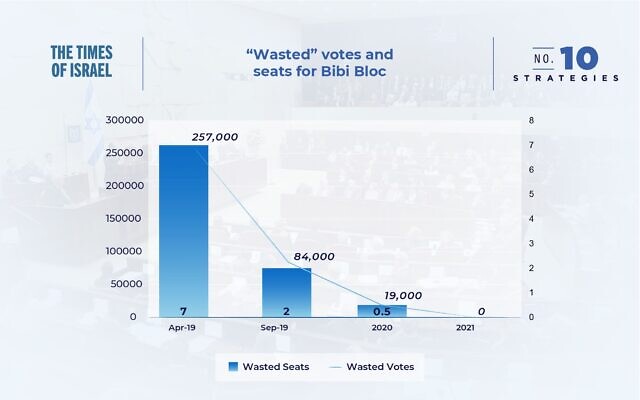

The first pillar has been to facilitate alliances between different parties within the bloc to ensure that – this time – no votes are wasted. Indeed the issue of wasted votes has been a fixation of Netanyahu’s ever since it prevented him from winning the first round of this election marathon in April 2019.

As seen in the graph below, this lesson has been learned, and the number of “wasted” votes from parties in the right-wing bloc has decreased from 257,000 (around seven seats) to zero in 2021.

‘Wasted’ votes for MK Benjamin Netanyahu-led bloc.

In order to maintain this, Netanyahu moved determinedly to ensure that Religious Zionism and Otzma Yehudit ran together this time, so as to avoid any wasted votes. While he has received huge criticism for these efforts – Otzma Yehudit is a far-right party that Netanyahu himself had previously avoided working with – on a political level, he was lauded for his acumen.

Then prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, right, speaks with then justice minister Ayelet Shaked in the Knesset, December 21, 2016. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Yet Netanyahu seems to have shown a blind spot when it comes to his former aide and long-time political adversary Ayelet Shaked and her Jewish Home party with whom he has stubbornly refused to engage. While originally it could have been argued that the party took votes from both blocs, it now has firmly established itself on the right. Shaked is generally polling around the 1.5-2% mark, well short of the threshold, but the equivalent of “burning” up to two seats for the Bibi bloc.

In such a close election, this oversight could be decisive.

2. Being more statesmanlike

This column has frequently discussed the pivotal battle for the “soft right” in this election, thought to be the only group of voters who could in theory be persuaded to move between the blocs. Whereas in previous rounds Netanyahu adopted a “base first” (even a “base only”) strategy, this time he has sought to appeal to this group of swing voters by toning down his more controversial statements and muzzling more extreme voices in his party. In short, he has tried to be more mamlachti (statesmanlike is probably the best translation).

The challenge here, though, is twofold. Firstly, having worked to promote and boost the profile of some of his more aggressive ministers over the last few years, it is hard to now hide them. And even if he does succeed in keeping them out of the limelight, there is a treasure trove of quotes in the archives for opponents to bring out to remind soft right voters of some of the views held by Netanyahu’s allies.

Second, Netanyahu’s long-time political mantra is to never abandon your base. And while there are various communications techniques to win back swing voters you may have lost along the way (the “sincere” acknowledgment of past mistakes being a favorite around the world), these don’t tally with the need to keep his base enthused.

3. Decrease Arab turnout

Netanyahu’s attempts to strike a more moderate, conciliatory tone is also relevant within the context of Arab turnout. Simply put, he is well aware that the lower Arab turnout is, the higher his chances of getting to 61. Netanyahu also knows that some of his more rabble-rousing, anti-Arab comments have, in the past, served to mobilize turnout in the Arab sector. So this time he has sought to lower the flames, not doing anything that could wake up the Arab sector, which currently is dominated by a sense of apathy.

There are clear signs of decreased Arab turnout – as discussed in a previous column – so whether or not he is responsible, this element of his strategy so far appears to be going to plan.

4. Stability

The fourth element has been a focus on a core message of stability, based on the idea that the most likely path to a stable government is if the pro-Netanyahu bloc wins 61 seats. This message of stability has also been adopted by other parties (clearly with similar polling data). Notably, Benny Gantz’s National Unity party is claiming in its campaign that only it can bring stability, and has thrust the issue to the forefront of its messaging.

Though it hasn’t yet necessarily translated into votes for the pro-Netanyahu bloc, that could well change in the final weeks when – after the Jewish festivals – the parties will spend the bulk of their war chests.

How effective has it been so far?

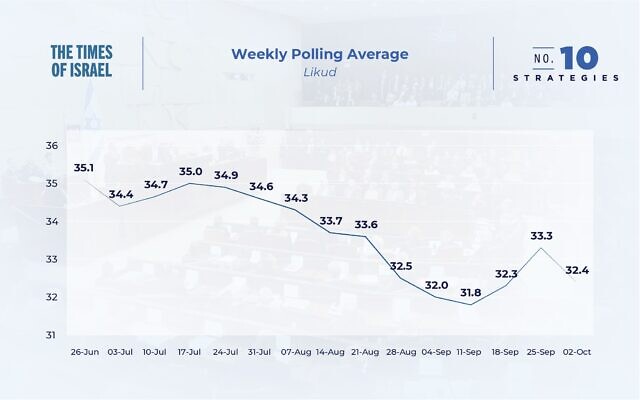

From the perspective of the Likud party alone, the campaign so far has been a disappointment.

Beginning with around 35 seats, its polling average has fallen almost every week, and now stands at 32.4, a drop of just over two and a half seats.

Likud weekly polling average.

When it comes to the blocs, however, the opposite is true.

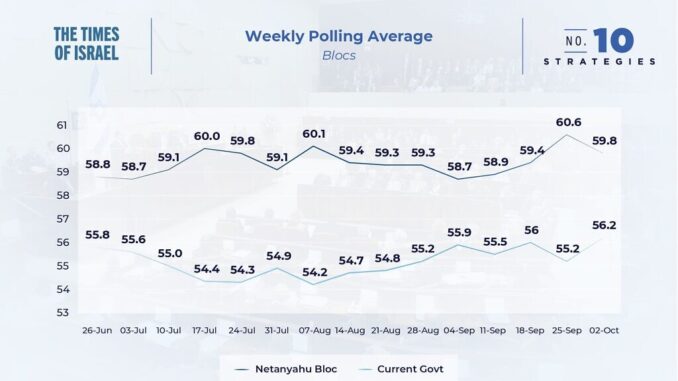

While the Likud vote has fallen, the pro-Netanyahu bloc has increased its polling, from 58.8 seats at the campaign onset to 59.8 today. This increase, however, is closely linked to the split in the Arab parties a few weeks ago, which led to an almost two-seat jump for the bloc.

Knesset blocs weekly polling average.

Indeed, this week there have been some signs that the effect of this split has begun to wane, as Netanyahu’s bloc has dropped by 0.8 seats (and Likud dropped by 0.9). Netanyahu would have hoped that the momentum gained over the past few weeks would help carry him to 61, but this week’s polling indicates that in fact, his numbers are on the slide, as the Arab vote has (for the time being) stabilized.

Looking at the 18 polls taken since the split in the Joint List, his bloc has got to 61 just four times, three of them with Direct Polls (more about the variance between polling companies here). In fact, in recent weeks the gap between polling companies has widened: The average of the Netanyahu bloc in the past two weeks is 61.75 with Direct Polls, and 59.6 with the other four companies combined.

So while his bloc is in a slightly stronger position than three months ago, Netanyahu is likely not much closer to 61 than he was at the start of the campaign.

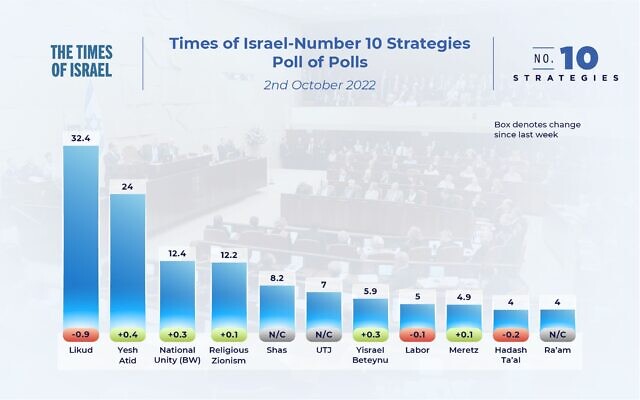

The state of the Israeli election campaign: Poll of polls, October 2, 2022, showing the number of seats parties would be expected to win if the election was held today, based on a weighing of the latest opinion polls.

How might Netanyahu close the campaign?

The upshot of this is that, in the final weeks of the campaign, the most logical closing strategy for Likud is one centered around boosting turnout from among its supporters (as we wrote last week about Yesh Atid). After four elections in quick succession, and with the number of voters genuinely open to moving between the blocs extremely limited, this is ultimately a mobilization – rather than persuasion – election.

Netanyahu understands this full well. As various analyses of the 2021 election have shown (such as this excellent article from the Israel Democracy Institute), there was a major drop-off in turnout from right-leaning and religious areas compared to 2020. For example, while turnout decreased by around one and a half percent in Tel Aviv and its upper-middle-class suburbs (which generally vote for the center-left bloc), it fell by between four and five percent in Likud-leaning towns and cities.

So while bloc switching is rare, there are a sizable number of right-leaning voters who have simply stopped voting in recent years. Were they to come back to vote this time, it could be the push Netanyahu needs to get to 61 seats.

His recent 1+1 message (each Likud voter should bring a friend to the polls) is an attempt to address this issue, and we should expect similar GOTV-based messages in the coming weeks. Interestingly, such messages are often highly targeted and therefore can fly under the media radar, meaning that we may well not know the aggressiveness – or effectiveness – of this approach until the results come in.

As we wrote last week, such a GOTV-based strategy is generally less interesting to read and write about, and is based on incremental gains rather than the sudden boost that effective advertising can sometimes have.

But in today’s highly polarized and fatigued political climate, both Netanyahu and Lapid are hoping it will be decisive.

—

* Full disclosure: The authors of this piece have recently conducted polling on behalf of Meretz.

Simon Davies and Joshua Hantman are partners at Number 10 Strategies, an international strategic, research and communications consultancy, who have polled and run campaigns for presidents, prime ministers, political parties and major corporations across dozens of countries in four continents.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.